Learning

The process of learning is concerned with establishing a store of information that can be used to guide future behaviour - the store of information gained through learning is known as memory. The importance of memory to normal human activity is evident in patients suffering from various neurodegenerative diseases, notably Alzheimer's disease.

The various kinds of learning can be divided into three main groups:

Simple learning : Modification of behaviour in response to a stimulus

Associative learning : Passive and operant conditioning

Complex learning : Imprinting, latent and observational

Learning can, and often does occur, without immediate change in behaviour. However, we can only be sure that a task has been learnt - stored in the memory and retrieved - if there is some modification of behaviour. In all types of learning, there needs to be a change in the strength of specific neural connections.

Simple learning

Simple learning is concerned with the modification of a behavioural response to a repeated stimulus. The response may become weaker as the stimulus is perceived to have no particular importance. This process is called habituation. If an unpleasant or otherwise strong stimulus is given, the original reflex response is enhanced, in a process known as sensitization.

Associative learning

In associative learning, an animal makes a connection between a neutral stimulus and a second stimulus that is either rewarding or noxious in some way. The chiming of a clock can be a reminder that lunch is due, or that it is time to go home. In this type of association, a neutral stimulus is associated with some more important matter. This kind of behaviour is not confined to humans - it can be found in many animals, and the first systematically studied associative learning by I.P. Pavlov was completed on dogs.

Pavlov paired a powerful stimulus such as food with a neutral stimulus, classically the ringing of a bell. After a number of trials in which the dog was fed immediately after hearing the sound of a bell, the animal would begin to salivate on hearing the bell in anticipation of being fed. This is known as a conditioned reflex - normal salivation in response to food is known as the unconditioned response. After establishment of the conditioned response, the ringing of the bell is sufficient for salivary response to occur. The process of establishing a conditioned reflex is known as passive conditioning.

In operant conditioning, an animal learns to perform a specific task to gain a reward or to avoid a punishment. In this respect, the protocol is different to the establishment of a classical conditioned response where an animal responds passively to pairs of stimulus delivered; this is more of an 'active' process. During operant conditioning, an animal may learn to press a level to gain a reward of a sweet drink or to avoid an electric shock. Initially, a naive animal is placed into the experimental chamber which is often an apparatus known as a Skinner box (named after B.F. Skinner, who discovered operant conditioning). The animal then explores its surroundings, and by chance it may find a level that leads to the delivery of a food pellet or some other powerful stimulus. After a short period, the animal learns to associate the pressing of the lever with the delivery of food or some other powerful stimulus. In this way, animals can be taught to perform quite complex tasks.

In both passive conditioning and operant conditioning, the animal learns to associate one stimulus with another. The reverse is also true - an animal may learn to avoid harmful experiences such as eating of poisonous foods by associating them with a particular colour, smell or adverse reaction (e.g. vomiting). This is known as aversive learning.

Complex learning

Complex learning is diverse in its nature. It includes imprinting, seen when young birds learn to recognise their parents by some specific characteristic. Latent learning, in which experiences of a particular environment can hasten the learning of a specific task (finding food in a maze) and observational learning (copying the task from someone).

Cellular mechanisms of learning

All animal behaviour is determined by the synaptic activity if the CNS, especially that of the brain. It would be logical to assume that there would be changes in synaptic connectivity following some learnt task. This approach is feasible in animals that have simple nervous systems and stereotyped behavioural patterns. Changes in the strength of certain synaptic connections have been demonstrated during the habituation and sensitisation of the gill withdrawal reflex of the sea-slug Aplysia.

The Aplysia gill and siphon withdrawal reflex (GSWR) is the involuntary, defensive reflex of the sea hare. The reflex causes the sea hares delicate siphon (tube-like structure in which water flows for locomotion, feeding, respiration and reproduction) and gill to be retracted when the animal is disturbed.

Habituation was observed when a weak/non-noxious stimulus was delivered repeatedly to the siphon. Stimulus every 90 seconds resulted in a rapidly decreased response. Delivering an electric shock to the tail, which was a different novel stimulus, the response was rapidly restored, and a dishabituation occur. Sensitization was observed when a strong noxious stimulus was administered to the tail.

Unfortunately, in mammals, the CNS is so complex that this direct association is not easy to achieve. Nevertheless, some brain regions, long-lasting changes in the strength of certain synaptic patterns have been reliably found following specific patterns of simulation. In some circumstances they are strengthened, while in others they are weakened.

Hippocampus

The hippocampus has been the subject of intense study, which has been implicated in human memory. The efficacy of synaptic connections between neurons of the hippocampus is readily modified by previous synaptic activity. This is precisely what is required of synaptic circuits that are involved in learning. Brief patterned stimulation leads to a very long lasting increase in the efficacy of synpatic transmission in several of these pathways that lasts for many minutes or even hours. This phenomenon has become known as long-term potentiation (LTP).

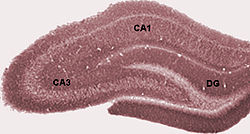

The basic neural circuit of the hippocampus consists of a trisynaptic pathway. It includes the perforant pathway, which is a projection from the entorhinal islands to the dentate gyrus. The mossy fibers, a projection from the dentate gyrus to CA3; and the Schaffer collaterals (the projection from CA3 to CA1). As is the case for intrinsic amygdala circuitry, the hippocampal circuit is largely unidirectional - CA3 does not project back to the dentate gyrus, nor do CA1 pyramidal cells project back to CA3. In the hippocampus, the outer layer is the molecular layer, the middle layer is the pyramidal layer, and the inner layer the stratum oriens.

The signals begin from glutamatergic inputs from the superficial entorhinal cortex (EC) layers (LII and LIII). The signal ends in the CA1 pyramidal neurons via the trisynaptic and monosynaptic paths; hippocampal back projections to the deep layers of EC complete the loop. Sensory signals drive the perforant path (PP, purple), inputs from EC LIII pyramidal neurons to distal CA1 pyramidal neuron dendrites (light blue). EC LII pyramidal neurons send inputs to dentate gyrus (DG, black), which sends mossy fiber axons (dark green) from the DG to the CA3 pyramidal neurons. The CA3 feeds onto the CA1 neurons through Schaffer collateral (SC, dark red) excitatory inputs. A major output of the hippocampus arises from CA1 pyramidal neurons, which project to lateral ventricles of the entorhinal cortex (EC). There is a 15-20ms timing of transmission from EC LII to CA1 through the trisynaptic path compared with that from EC LIII to CA1 monosynaptic path.

Entorhinal cortex (EC)

Located/part of the brains allocortex (10% of brain matter, 90% is taken up by the neocortex. It is characterised by having only three or four cortical layers, in contrast with the six cortical layers of the neocortex). It is located in the medial temporal lobe, whose function include being a widespread network hub for memory, navigation and perception of time. The EC is the main interface between the hippocampus and the neocortex.

Pyramidal neurons

Pyramidal neurons are a type of multipolar neuron found in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus and amygdala. Pyramidal cells are the primary excitation units of the mammalian prefrontal cortex and the corticospinal tract. The main structural feature is the conic shaped soma, or cell body, after which the neuron is named. Other key features of the pyramidal cell are a single axon, a large apical dendrites, multiple basal dendrites, and the presence of a dendritic spine.

Dentate gyrus

The dentate gyrus is part of the hippocampal formation, located in the temporal lobe. The dentate gyrus is part of the trisynaptic circuit and theorised to be the location of new episodic memories, the spontaneous exploration of novel environments alongside other functions. The dentate gyrus, like the hippocampus, has three distinct layers : an outer molecular layer, a middle granule cell layer, and an inner polymorphic layer.